Wikipedia

- Details

- Written by Helen Buyniski

- Category: Wikipedia

Over half a billion people visit Wikipedia every day. The site enjoys top billing in Google search results, and has all the trappings of a reliable source. It’s an encyclopedia, after all - like Britannica, it’s expected to have accurate, trustworthy, unbiased information. But a real encyclopedia doesn’t permit anonymous editors with no scholastic background to edit whatever they please. Even the crowd-sourced, fair and unbiased encyclopedia that Wikipedia claims to be doesn’t permit the sort of pay-for-play editing and uneven application of the rules that have made Wikipedia a goldmine for propagandists and a nightmare for unorthodox figures in every discipline.

All this happens with the full blessing of Jimmy Wales and the Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit to which he gifted Wikipedia nearly two decades ago. The Foundation is run by executive director Katherine Maher and a growing stable of paid employees, none of whom are paid to write encyclopedia articles, and overseen by a hand-selected board of trustees, most of whom remain utterly unknown to the vast majority of internet users who consume - deliberately or indirectly - Wikipedia content daily. This is their story. The difference between what you are about to read and the bios featured on Wikipedia is that these are accurate and well-sourced.

The Wikimedia Foundation, according to its website, wants you to “imagine a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge.” But spend a few hours on its flagship product, Wikipedia, and you can see just how loosely that term - “knowledge” - is defined. Wikipedia seems not to believe in the concept of truth, only verifiability - anything can be included in its articles so long as it has been written in a “reliable source.” And any source can become reliable if enough editors justify the decision to make it so. This nightmarish postmodernism has given rise to one of the preeminent repositories of disinformation on the internet.

Wikimedia Foundation trustees don’t bother themselves with such issues, of course. Many may be on the Foundation’s board in the hope of basking in the reputational glow of the group that runs the fifth-most popular website in existence, or because they want some say in guiding the future of an incredibly powerful website without having to answer to either an employer or the public. Certainly they don’t expect to be taken to task for facilitating the reputation-destruction mechanism that Wikipedia has become, or have their own histories scrutinized. But that is precisely what we plan to do here, in the hope that they think twice going forward about associating themselves with such a noxious, malevolent organization.

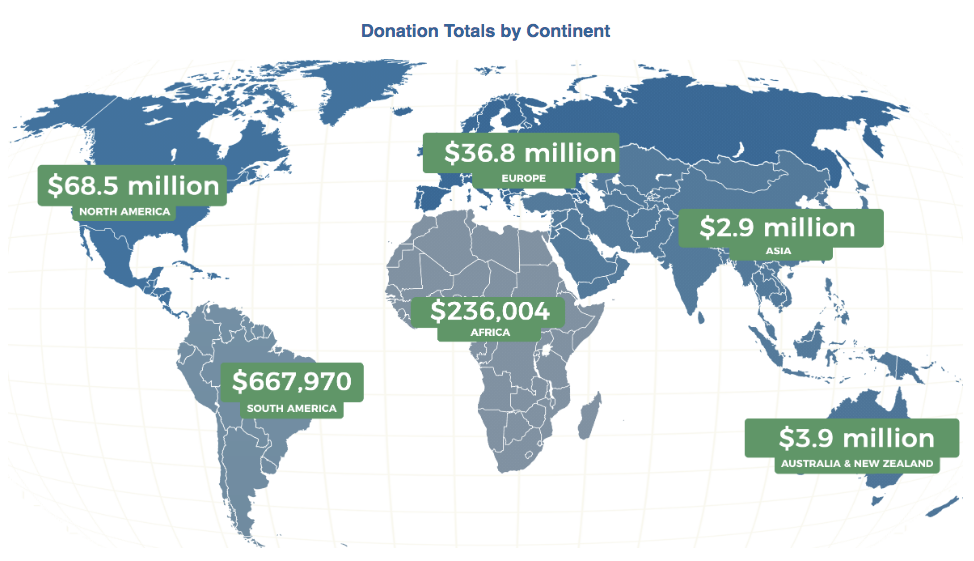

The Wikimedia Foundation begs for money via intrusive banners across the top of Wikipedia pages, banners which implore the viewer to give just a few dollars lest the site be shut down completely for lack of funds. These banners are the internet equivalent of a “beggar” who rises after a day sitting with a cardboard sign on the sidewalk conning hardworking people out of their spare change and steps into a Ferrari, from whence they’re chauffeured to their posh Upper East Side penthouse. The Wikimedia Foundation took in over $112 million last year in donations,1 and a Smithsonian article from way back in 2013 valued the site at “tens of billions of dollars,” with a replacement cost of $6.6 billion.2 Not a bad deal for a site that pays its content creators - the editors who write the articles - nothing, and indeed takes their money as well as their time through guilt-inducing begging banners, slurping up many times what is required to run the site every year.

The Foundation, unlike the editors, is largely parasitic - its employees, whose numbers swell with the excess cash taken in with every fundraising campaign, provide little to no value to the average Wikipedia reader, while its trustees do little more than pad their resumes with the Foundation name. Indeed, in our opinion, instead of providing value, they subtract it - whether through absconding with Foundation funds to pay for their vacations, or running roughshod over Wikipedia rules to push their pet agenda.

Maria Sefidari

Maria Sefidari (Wikipedia alias Raystorm), chair of the Board of Trustees, has long been involved in managing the Foundation’s money, serving on multiple governance committees before becoming a trustee. She has an impeccable social-justice pedigree, having founded Spanish Wikipedia’s LGBT WikiProject and a Spanish-language women’s editing group. Sefidari came under the microscope recently when her erstwhile wife/girlfriend, Laura Hale, allegedly used her connections to get a longtime Wikipedia administrator, Fram, banned from editing after he corrected her sloppy work one time too many. Fram’s ban was handed down by the all-powerful Wikimedia Foundation for nebulous reasons of “abuse,” but unlike the usual permanent bans the Foundation hands out for unpardonable crimes, it was only temporary. Moreover, the Foundation’s Trust & Safety team had not discussed the matter with the Arbitration Committee, the editorial disciplinary board, at all before unilaterally blocking the editor. Fram did not suffer fools gladly and could be short with editors who repeatedly violated the rules; he had been hauled in front of disciplinary committees more than once over the previous years,3 but many attempts to bring proceedings against him were declined. When the “evidence” against Fram finally emerged, the “over a dozen people” who’d supposedly complained were found to have done so over a six-year period; many so-called “victims” denied having been harassed or hounded at all.4

Fram’s allies at Wikipedia did what the site’s editors do well - research - and uncovered a handful of minor altercations with Hale, an editor who could never seem to get the hang of the encyclopedia’s rules. Fram had been firm but not cruel with Hale, telling her to stop editing until she could grasp concepts like plagiarism and coherence - and Hale had, some editors suggested, run crying into Sefidari’s arms. For months, she ran a banner on her user page explicitly directed at Fram, telling him to keep away unless he was prepared to interact through a handful of editors of her choice and/or the Trust & Safety team.5 Hale was an unabashedly terrible editor, copy-pasting an incoherent swathe through paralympic athletes, obscure elements of feminism, abortion minutiae, and other marginal topics with a social justice aura that were likely to endear her to Sefidari and the board. And while some said she had a bit of a history as an internet grifter, crying sexism whenever a community got wise to her machinations,6 that was a feature, not a bug, for the Foundation, which used a poorly-written paper she’d written around the time of the GamerGate controversy in 2014 in a list of material its nascent “Support and Safety” (soon to become Trust and Safety, the division which banned Fram) team compiled about online harassment (likely due to the dearth of Wikipedia-specific material).7 When the Foundation wanted to expand its range of bannable offenses to include “incivility,” it was only natural they’d reach for Hale’s complaints, several editors alleged.8

Even if the Hale story is pure fiction - and Sefidari not only denies it but “protests too much,” accusing its authors of “bad faith” and involvement with the dreaded GamerGate9 (how could anyone possibly think a trustee would intervene on behalf of their spouse?)10 - Sefidari’s hands aren’t exactly clean. When first appointed as a trustee, Sefidari helped change the voting rules for the selection of two trustee positions so that Wikipedia User Groups gained the voting rights that had previously been limited to Chapters. This move benefited Hale, who’d started two user groups and was thus able to vote on behalf of one in the Foundation’s 2019 board election. Researchers on Wikipedia criticism board Wikipediocracy turned up several more conflicts of interest involving Hale and Sefidari, many of which involved the latter steering Foundation grants the former’s way. With Sefidari’s help, less than a year after joining her paramour in Madrid in 2013, Hale was able to first convince the Spanish Paralympic Committee into sponsoring her as a Wikipedian in Residence (a sort of official editor for nonprofits), despite not speaking Spanish,11 and then managed to use that title to convince the Wikimedia Foundation to pay her way to a paralympic alpine skiing event (bringing Sefidari as guest, for a total of €1035).12 Hale had been milking the Foundation for a while - along with her previous roommate/mate, Australian editor Ross Mallett (Hawkeye7), she’d wheedled $11,000 out of them to attend the London 2012 Paralympics.13 She’d eventually get the Foundation to pay for trips to Argentina, London, Amsterdam, Slovakia, and Berlin.14

Sefidari’s Wikimedia Foundation bio is rather bold about these extracurricular activities and her casual use of Foundation cash, hinting that she “travels around the world” “in her spare time” - though neglecting to mention this travel is often done on the Foundation’s dime. Nor does the Foundation get its money worth out of these junkets, since Wikipedia is based on secondary sources alone (i.e. articles that have already been written in so-called “reliable sources”) and Wikinews’ readers are vanishingly sparse. Worse, Hale may have taken cash from the Australian Center for Paralympic Studies to mass-create the thousands of poorly-written articles that set Fram and other editors’ teeth on edge,15 creating the kind of conflict of interest that is supposed to be either banned outright or at least acknowledged on a Wikipedia editor’s user page.

Hale even rewarded her wife for entrée into the upper echelons of the Foundation by writing a lengthy and rather ridiculous article on “Lesbians during the socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero,” prominently featuring Sefidari (with photo) as “one of the major writers of the English Wikipedia article, ’Same-sex marriage in Spain,’ updating the article often in 2007.” Nothing says ‘notable’ like editing a Wikipedia article, especially ‘often!’ Digging deeper into Sefidari’s background, editor Vigilant at Wikipediocracy claimed he was “almost certain” that Sefidari’s academic credentials were “completely fabricated.”16 There is no evidence she has worked as a professor, aside from teaching a “vanity class” or two at the university where she claims to be studying for her PhD.17 But for all the couple’s transgressions, “increased activity in covering disability related issues and sensitivity in making Wikipedia more disability friendly” - along with increased activity in the LGBT and feminism subject areas - was considered more important than following the rules.

It may seem unfair to scrutinize Sefidari’s life in this manner; however, she is the chair of the Foundation’s board of trustees, and as such must be aware of conflicts of interest, lest she bring the entire organization into violation of the regulations governing charities (either in the US or elsewhere). According to California state law governing nonprofits (and the Foundation is headquartered in California, even though Sefidari and Hale live in Spain), “a staff member who is affiliated with a prospective vender, consultant, or grantee shall abstain from participating in any decision involving that vendor, consultant, or grantee,” and specifies that in a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, “no part of the net earnings of [a foundation] inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.” Regulations also bar “excess benefit transactions” in which a charity provides excessive economic benefits to a “disqualified person,” a term that includes spouses and relatives of board members. Board members are also required to divulge conflicts of interest on at least an annual basis18 - for all Sefidari’s defense of Hale in Wikipedia’s talk pages, she never makes reference to the pair’s romantic relationship (except to deny it amid the Fram controversy). Sefidari’s actions don’t just cast the rest of the organization into disrepute - they could jeopardize the Foundation’s tax-exempt status.

Because Wikipedia editors are almost exclusively white males from the global North, the Foundation is desperate for diversity - and it will set its vaunted principles on fire to get it. Whether it’s embracing Sefidari and Hale, or putting out a call on its website for nonwhite editors to “help correct history,” the Foundation wears its desperation on its sleeve.19 Thus it’s no coincidence that the Board’s gender balance is skewed opposite of its editors’, with two thirds of the trustees being female - or claiming to be.

Esra’a al-Shafei

Esra'a al-Shafei is a Bahrainian trustee represented online solely by a cartoon illustration - supposedly because her work as a human rights activist and pro-LGBTQ organizer in the Middle East has put her at risk. This intrigue has the benefit of getting the 33-year-old activist praised as “brave” - to the point of winning the “Most Courageous Media” prize from Free Press Unlimited. However, one could be forgiven for questioning her bona fides, especially after the revelation several years ago that a supposedly lesbian Syrian woman who regularly called out President Bashar al-Assad on her blog Gay Girl in Damascus was actually a middle-aged American man living in Scotland.20 A sense of déja vu begins to set in when one learns that the “Most Courageous Media” prize appears to have been awarded exactly once, in 2015, to al-Shafei. Her identity checks out in other ways, however, mostly concerning the wide array of prizes she has received. In 2013, she was honored by the royal family of Monaco for her role in the Arab Spring, having created a platform called CrowdVoice to curate grassroots reports from protests worldwide (the platform recently folded after congratulating itself for serving its purpose - great news, oppressed peoples of the world, your struggles are over!).21

Other groups that have showered her with money include the Shuttleworth Foundation, the Knight Foundation (which has also given generously to Wikipedia, and whose director Raul Moas was involved in USAID’s efforts to build a Twitter clone in Cuba called ZunZuneo to foment a “color revolution” echoing those of the Arab Spring22), and the Dutch government, which awarded her the Human Rights Tulip. The Dutch government has proven itself a poor judge of character in the Middle East, however, awarding aid to 22 “moderate rebel” groups in Syria from 2015 to 2018, grants that continued long after many of these groups' ties to al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups were exposed.23

Al-Shafei first surfaced in 2006 at the helm of Mideast Youth, an advocacy group for LGBT young people in the region, which later changed its name to Majal and expanded its remit to include other targeted ethnic and social groups in a way that conveniently overlapped with the activities of the US military and State Department in the region. By 2007, it had spawned an “Alliance for Kurdish Rights” - NATO’s preferred group for fomenting regime change in Syria, Iraq, Turkey, and Iran, where it has dreams of cobbling together a client state out of the most resource-rich parts of those countries (and has already begun the process with Iraqi Kurdistan in that country’s north) - and “Middle East Youth Farsi,” shut down two years later in the midst of the failed US-backed “Green Revolution” in Iran, ostensibly “in order to protect our members in Iran.” Majal gave birth to CrowdVoice in 2010 in the midst of the Arab Spring, while the organization registered itself in the Netherlands in 2012 “in order to protect our finances from being frozen by regional governments.” The timeline suggests Majal is affiliated with one of the many soft-power tentacles of US Empire, an extensive network of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) funded by shell companies and nesting-doll subsidiaries of USAID and NED (as well as obscure prizes and fellowships) to foment unrest in targeted countries. Running an advocacy group for LGBT youth in a Muslim country is squarely within the sweet spot for the US’ regime-change industry, and al-Shafei’s made-for-TV rhetoric - she’s all about “revolutionizing the young people” and “changing the region’s status quo” by “living up to the full potential of the internet” - is right up their alley.24

![]()

How a then-teenage Bahrainian girl taught herself to use the internet well enough in just six years (she claims to have gained internet access “in the early 2000s”)25 to create her own online platform, then hooked up with the myriad sources of funding she has accessed, from Harvard University to the Rockefeller Foundation, is never satisfactorily explained in the handful of interviews she’s done (her arms surprisingly bared in western clothes, her face always kept carefully out of frame). Soft-spoken, with just a hint of an Arabic accent, her biography as she relates it - becoming one of Bahrain’s leading LGBT activists while living under the roof of parents who supposedly know little about her work beyond that she’s “in human rights” - stretches the limits of credulity, as do her reasons for taking what is supposedly such a dangerous career path - she claims witnessing the “inhumane treatment” of migrant workers as a child, plus stereotypical portrayals of Middle Eastern youth in the media, led her to forsake a life of ease for the hunted life of an internet rebel.26 It’s easy to see how this too-perfect figure, orbited by deep-pocketed foundations orders of magnitude richer than itself, appealed to the Wikimedia Foundation, which hired the young activist in December 2017, showering her with praise (“her achievements exemplify how intentional community building can be a powerful tool for positive change, while her passion for beautiful and engaging user experiences will only elevate our work”).27 Al-Shafei returned the flattery and then some, claiming that in her first encounters with Wikipedia, shortly after coming online, she “felt that the true purpose of the internet was realized” (the internet she’d known for less than a year, apparently). Wikipedia inspired al-Shafei’s own platforms, Mideast Youth, Majal, and all their branches, she claims.

How did the Wikimedia Foundation chance upon the camera-shy cartoon crusader? The Foundation does not give away its secrets, but she could have rubbed shoulders with Jimmy Wales at Davos - the World Economic Forum named her one of “15 Women Changing the World in 2015,” and has since appointed her to its Global Future Council on Human Rights and Technology28 - or as early as 2008, when she received an award from Harvard Law’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, where Wales is a fellow. Al-Shafei was embraced into the bosom of Wikipedia as a keynote speaker to 2017’s Wikimania conference in Montreal. There, she wowed the Foundation with a talk on “Experiences from the Middle East: Overcoming Challenges and Serving Communities.”.29 While all the other speeches were livestreamed and archived for later viewing, al-Shafei’s was shrouded in secrecy, with attendees warned that attempting to photograph or record her would result in ejection from the conference. “Due to the nature of al-Shafei’s work, online photos may endanger her safety in her home country,” the conference notes state with obvious titillation.30

James Heilman

James Heilman is a Canadian emergency room physician who runs WikiProject Medicine (WPM) and the WikiProject Med Foundation, the site’s primary vehicle for interfacing with Big Pharma. WPM came up with the MEDRS - short for “medical reliable sources” - guidelines that require editors editing health-related articles to use a higher standard of source than typical articles. It’s a smart rule, aside from the mile-wide loopholes carved into it by the FRINGE guideline appended by so-called “Skeptics” who demand the right to libel alternative medical practitioners they deem “lunatic charlatans” - a term that was actually enshrined in semi-official Wikipedia policy after co-founder Jimmy Wales used it to repudiate a petition from a group of practitioners begging for fair treatment.31 The ironically-named activists who call themselves Skeptics are characterized by a quasi-religious regard for orthodox medical “science” - which in their view is unchangeable, unquestionable, existing in a state of timeless perfection - and a seething hatred for medical practices that haven’t made it into the mainstream, even (especially) if they have been shown to work. If a practice or healer does not fit into current medical orthodoxy, it is susceptible to being edited under FRINGE rather than MEDRS, at which point even self-published sources that normally aren’t permitted as Wikipedia citations can be weaponized against the hapless article subject. Heilman is a relentless proselytizer, singing the praises of Wikipedia’s medical accuracy32 as he spearheads the Foundation’s efforts to insinuate Wikipedia into real-world health agencies. Accordingly, he has encouraged and organized editing initiatives at the National Institutes of Health, the National Libraries of Medicine,33 even pharma conglomerate GlaxoSmithKline. The World Health Organization is even collaborating with Wikipedia on its revision of the International Classification of Diseases into the ICD-11,34 a sobering thought given the pro-pharmaceutical leanings and general inaccuracies rampant in Wikipedia’s medical content.

Despite Heilman’s proclamations that Wikipedia has brought about a new dawn in medicine, the site’s medical articles are riddled with verification issues and apparent conflicts of interest. Informed that Wikipedia was unwittingly mirroring a crowdsourced pharmaceutical database called Drugbank that had gotten its own information from Wikipedia - a circular-reporting phenomenon called citogenesis - Heilman took no action beyond adding Drugbank to a list of mirror sites and calling Drugbank to complain about its sloppy sourcing.35 Yet this is the website that is increasingly supplanting traditional medical resources for students and doctors. Faced with the gulf of missing and inaccurate information, Heilman has repeatedly tried to push the blame onto medical professionals, chiding them for not making updating Wikipedia a part of their job.36 Of course, doctors who try to bring the encyclopedia up to date on naturopathic treatments, or the benefits of supplements, will find their contributions trashed and perhaps their usernames topic-banned from the medical subject area - because their work in alternative medicine creates a “conflict of interest.” Heilman's own medical career, of course, is excused from any such conflict, as are the editors who hail from health agencies and drug companies who’ve passed through Wikipedia’s train-the-experts programs.

Heilman was quick to throw even his fellow worshipers of orthodox medicine under the bus last year in a rush to seal a deal with video production company Osmosis that would replace high-traffic medical articles with 5-10 minute “explainer” videos prominently featuring the company’s branding. When the first videos were unveiled in March 2018 after three years of sub-rosa collaboration, furious editors rushed to delete the monstrosities (which in addition to pushing vaccines and orthodox drug treatments also included inaccurate and outdated medical information).37 The deletions were reverted by Heilman and another editor working for Osmosis as the company promised to fix the problems - meanwhile leaving the erroneous medical information front and center, in many cases replacing well-sourced articles crafted over the years by the WPM spell out community - and when editors continued to object, Heilman tried to have one of the dissenters banned. Finally, Heilman seemed to cave, convincing Osmosis to remove all mention of the project from their website and removing the clips from the offending articles - but a month later they had returned as “works in progress,” allowing editors to leave feedback.38

WIkiProject Medicine hasn’t just encouraged health regulators and pharma reps to try their hand at editing - it has weaseled its way into medical schools around the world, from the University of California at San Francisco to Tel Aviv University’s Sackler School of Medicine (yes, those Sacklers of OxyContin fame - when you’re suspected39 40 of conducting pharmaceutical experiments on imprisoned Palestinians considered second-class citizens under your legal system,41 opioid profiteering is small potatoes) Heilman runs a massive translation program designed to spread the western medical viewpoint around the world,42 which sounds benevolent until one remembers that the US doesn’t just have the highest-priced healthcare in the world - it has one of the lowest life expectancies in the developed world, too.43 A concurrent project seeks to audit Wikipedia’s medical articles to ensure they their content conforms to so-called “Evidence-based Medicine” (EBM) - another term that sounds utterly benign, even desirable until one observes that its practitioners rely not on clinical evidence, treatments that have been shown to cure patients, but on textbook evidence, treatments that “should” work based on established medical orthodoxy. EBM’s primacy in Wikipedia is maintained by the (profoundly unskeptical) Skeptics, who are allowed to run rampant under Heilman’s sympathetic rule. Heilman in 2016 revealed that WikiProject Medicine was working with Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders). The project apparently involved translating articles and creating a set of standards to be imposed across language wikis; it was connected to Wikipedia Zero, the Foundation’s effort to penetrate areas with little to no internet access by offering devices capable of accessing a handful of websites, one of which is (of course) Wikipedia. One can imagine a tragicomic scenario in which a team of Wikipedia-educated doctors descend on some poor war-ravaged country and extend the victims’ suffering by limiting their treatments to Skeptic-approved “Science”-Based Medicine - while some knowledge is certainly better than none, handing a doctor in an isolated village a device capable of accessing only Wikipedia means that doctor must now choose between treating patients as they are accustomed to doing, or trusting Wikipedia - since they can’t check references or use a search engine to compare what non-Wikipedia sources say.44

Heilman's one-two punch of mainstreaming and disseminating dubiously verifiable pro-Big Pharma material has reportedly already convinced Indians in Malappuram to embrace vaccines in the face of so-called “fake messages” on WhatsApp and Facebook45 - disregarding India’s appalling history with western vaccination campaigns. Over half a dozen children died and hundreds were sickened following a 2009 Gardasil vaccination campaign in Andhra Pradesh; two more were killed and many more injured in Gujarat following a Cervarix campaign that same year. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), which conducted the trials, nevertheless declared them a roaring success, though a later investigation found consent for the vaccinations was often obtained illegally and the illnesses and deaths were largely covered up or explained away as unrelated to the shots, assisted by local government. The American NGO that carried out the studies on behalf of the BMGF, the Orwellian-sounding Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), was reportedly in talks with the Indian government to include the HPV vaccine in the country’s Universal Immunization Program, an initiative that fortunately ran aground on the bodies of its victims.46

But the BGMF didn’t stop there. In 2011, a five-in-one shot called Pentavalent (including diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, and haemophilus influenza type b) was unleashed on the population. Infants began dying after vaccination - the Indian health ministry admits to 54 - and Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Vietnam actually stopped using the shot after similar horrors. In neighboring Pakistan, a 2011 report blamed the BMGF-funded Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) for 5,417 cases of polio in children it had vaccinated the previous year.47 The report suggested curtailing GAVI’s ability to administer vaccines to Pakistani children. With history like this, Indians are wise to hesitate before inviting Big Pharma into their veins once again. Yet Wikipedia’s feelings on “vaccine hesitancy,” an Orwellian psychological condition that appears to have been invented to pathologize parents’ negative reactions to learning about vaccine side effects,48 are unremittingly hostile, and “Doc James” Heilman is no exception. The pharmaceutical crusader’s certainty he is right is matched only by the likelihood he is wrong: in 2014, the same year an IMS Health study found Wikipedia was the #1 medical resource for doctors and patients alike,49 another study - this one from the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association - found that the site’s articles on 9 out of 10 of the costliest medical conditions in the US contained serious errors when compared to peer-reviewed medical literature.50 Heilman claims he got involved in Wikipedia in 2006 “after coming across a poor quality medical article”51 - if 9 out of 10 are poor quality now, what were they like before he got involved?

Nataliia Tymkiv

Nataliia Tymkiv is the board’s resident Ukrainian, serving as both a Foundation trustee and the Financial Director of the Centre for Democracy and Rule of Law (CEDEM), a Ukrainian “media policy and human rights nonprofit.”52 CEDEM was established as the Media Law Institute in the aftermath of Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution but glided effortlessly through the US-backed 2014 Euromaidan color revolution and has nestled itself comfortably into the Poroshenko puppet government, taking advantage of the upheaval to get a law concerning a public service broadcasting system passed that it had been pushing for nearly a decade. Judging by the organization’s website, it is wholly a creature of US foreign policy, self-described as “a think-and-act tank, which has been working in the civil society sector of Ukraine since 2005.”53 While the term “civil society” is often a red flag indicating USAID involvement, one doesn’t even have to guess with CEDEM - USAID is actually listed on their “partners” page, alongside Radio Liberty, a NATO-backed broadcaster.54

With that pedigree, it’s no surprise that Tymkiv is an administrator on Ukrainian Wikipedia. She also became treasurer of Wikimedia Ukraine in 2012, just a year after first contributing to the wiki, and moved up to Executive Director of Wikimedia Ukraine the following year. In 2015, she made vice-chair. This is an extremely rapid rise for a normal organization, though Wikimedia Ukraine no doubt has fewer members than many of the more trafficked language wikis. But Tymkiv is an effective Wikipedian - that same year, she, as executive director of the Ukrainian Wikipedia, and with the help of CEDEM’s predecessor, won a court case releasing a list of monuments and cultural sites in the country.55

Tymkiv isn’t just good at legal matters. Her bio notes that she oversaw the “building and maintaining” of “donor, partner and community relationships” - with donor coming first. It’s worth noting that at least two major financial backers of the Foundation56 57 were also major boosters of the violent 2014 coup in Ukraine. Pierre Omidyar58 59 and George Soros60 61 are both credibly implicated in funding the uprising and the Foundation appears to have followed suit in its support for the regime change. Jimmy Wales himself took the stage at a conference in Yalta less than a year after Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was forced to flee the country, calling on Ukrainian Wikipedia editors to "target both on-line and in physical environment the Russian speaking Wikipedia community in order to enable cooperation…so that Wikipedia remains the way of alternative views, alternative statements" - an order that could be interpreted as encouraging his loyal subjects to propagandize Russian readers about Ukraine.62

The fact that Tymkiv was treasurer of Wikimedia Ukraine, soliciting donations to expand her fiefdom, at the same time that Omidyar, Soros, and the usual cadre of regime-change fat-cats (several of whom were already Foundation donors) were funneling money into ‘democracy-promotion’ in Ukraine, suggests a strong likelihood of cross-pollination. She hinted in her 2016 candidate statement for appointment to the international board that she is active “not only locally” in Wikipedia - indicating she had interests outside Ukraine already, making her more than a provincial token - and included an endorsement from the virulently anti-Russian Estonian Wikipedia. Was Tymkiv given a seat on the international board in gratitude for her service - or perhaps to ensure her silence?

Shani Evenstein Sigalov

Shani Evenstein Sigalov is an Israeli educator pushing for the inclusion of Wikimedia projects in education, leading entire academic courses based on editing Wikimedia projects in the vain hope of giving Wikipedia some sheen of academic legitimacy, even though anything editable by anyone would seem to be necessarily unreliable in an academic context. Sigalov claims to have launched the first for-credit medical school course involving contributing to Wikipedia, with her students becoming responsible for a mind-boggling 10% of the medical content on Hebrew Wikipedia. She also launched the first academic course on Wikidata, in 2018 - a database even less reliable (because completely unsourced) than Wikipedia that is known to be riddled with errors, even libel, because few users bother to police its enormous data hoard for “vandalism” - deliberately-inserted errors.63 Is this malleability why she’s now getting her PhD in “Wikidata as a learning platform”?64 She is also a former board member of Wikimedia Israel, currently run by Itzik Edri, who worked as head PR man for former Mossad agent Tzipi Livni when she was chair of Israel’s Hatnua Party.65 While Livni resigned after several years in Israel’s secret intelligence service, “citing the pressures of the job,”66 one never really leaves the Mossad any more than one leaves the CIA, and the fact that Wikimedia’s chairman was the public face of a Mossad agent should at least raise a few questions about that chapter’s cozy relationship with the top brass at the Wikimedia Foundation.

Former Foundation director Lila Tretikov traveled to Israel in 2015 and gushed for local media about how the country’s schools were “teaching with Wikipedia,” perhaps a necessary cover for the Israeli Defense Force division devoted to social media manipulation67 (which includes Wikipedia) and the many non-official Israeli groups determined to “make Wikipedia balanced and zionist in nature” (an actual quote from the director of one of these projects, Naftali Bennett - and if the name sounds familiar, it’s because he went on to become Israel’s Education Minister)68 who would also receive and benefit from the “special translation tool” she gifted the Israeli chapter. The Hebrew Wikipedia isn’t terribly active - it had about 30 edits a day in 201569 - most likely because most of the Israeli editors are working on the English (or German, or Arabic) Wikipedias. Sigalov’s students have written “hundreds” of articles “in Hebrew and Arabic” - though the press release announcing her addition to the board does not break down that number into how many in each language, or - most tellingly - the subjects on which they made their mark.70 And Sigalov, as an “EdTech [education technology] innovation strategist” with postgraduate degrees from Tel Aviv University, has likely met with Bennett himself, a meeting in which it would be surprising if they didn’t swap stories about their Wikipedia exploits. The two appear to have attended the same conference in June 2016.71

Sigalov told the Wikimedia Foundation that she had never even heard of Wikipedia until a friend dragged her to 2011’s Wikimania conference in Haifa.72 She claims she fell in love at that first conference, joined Wikimedia Israel on the spot, and almost immediately became Projects Coordinator for GLAMWiki (Galleries, Libraries, and Museums). She was chair of WikiProject Medicine before her ascension to the international board, hence responsible for suppressing non-pharmaceutical methods of healing in the same manner as her fellow trustee James Heilman. Was it her nationality, her focus on “gender and diversity gaps” - still a major cosmetic blot on Wikipedia’s reputation - or her determination to shoehorn Wikipedia into education that gave her such momentum through the ranks?

Dariusz Jemelniak

Dariusz Jemelniak is a Polish professor behind a magisterial whitewash of Wikipedia ethnography called “Common Knowledge,” which insists in its introduction that despite first appearances, Wikipedia is not biased at all. In lending his name and prestige to such a book, he ensured no one would come around to write another one on the same subject for a long time - long enough for the Foundation to sink its teeth into the very fabric of the internet, along with education and medicine. Better yet, the book costs $30 and is published by a university press, making it next to impossible anyone will stumble across it accidentally.73 Not to imply a quid-pro-quo, but Jemelniak published Common Knowledge in 2014, and was elected to the Board of Trustees the following year. He lends a credible academic patina to an organization desperately in need of it, having served as a professor at Cornell, Harvard, MIT, and UC-Berkeley in addition to his native Kozminski University. He’s also a fellow of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center, alongside Jimmy Wales; fellow trustee Esra’a al-Shafei has received an award from the Center.

And Jemelniak has done his share of kowtowing to capital-D diversity - a short-circuiting of the rare meritocracies left in western society that coopts the struggle of actual marginalized people to give grifters a leg up - publishing a 2016 paper called “Breaking the Glass Ceiling on Wikipedia” that called for “aggressive reforms bolstering women’s sense of agency.” The nature of those reforms are not laid out in his paper, but in December 2016, the Foundation “formally committed” to “eliminating harassment, promoting inclusivity, ensuring a healthier culture of discourse, and improving the safety of Wikimedia spaces.”74 This all sounds quite noble on the surface, but in practice the Foundation’s obsessive focus on “harassment” is what birthed the Fram affair, as described above in the section on trustee chair Maria Sefidari. That same month, Sefidari herself declared Wikipedia was to ramp up its focus on inclusivity and “safe spaces.” The statistic she presented - that over half of Wikipedia users surveyed reported decreasing their editing because of harassment - didn’t even begin to try to define harassment, or address the weaponization of the concept.75 Laura Hale, Sefidari’s prickly spouse, had authored a different paper back in 2014 describing harassment of women on Wikipedia, but defining the word to include everything from use of the word “cunt” as an insult to use of “gendered generics,” i.e. “if the user wanted to add a source, he would have done so.” Hale also concluded that “interventions need to be tried to change the climate on English Wikipedia,” coming not only from the Foundation but from outside “feminist groups, universities, non-profits and existing social justice groups online”.76 Jemelniak’s paper, like his previous ethnography of Wikipedia, served to legitimize the Foundation’s attempt to reposition Wikipedia for the hyper-PC “social justice” power structure in a way that Hale’s could not.

The Foundation’s ambitions are, quite frankly, boundless: it wants to form “the essential infrastructure of the ecosystem of free knowledge.”77 That Jemelniak serves on the steering committee of the Internet Governance Forum, the UN-founded agency that serves as a sounding-board for international public policies governing the future of the internet, gives the Foundation entrée into the realm where the decisions shaping the internet’s future are made. Rubbing shoulders with NGOs and corporations, Jemelniak has a strong position from which to advocate for Wikipedia - as an educational resource, as a fact-checker, as a reputational barometer. These are not idle threats - Google already advises its “raters,” the low-paid contractors who shuffle through websites to assign algorithmic values to them and have the power to memory-hole inconvenient voices, to use Wikipedia to assess the trustworthiness of a website proprietor.78 This could have been an inside deal between the two companies - Google and Wikipedia have always had something of an incestuous relationship disguised as a rivalry. But given the Foundation’s efforts to insert itself in such base-level internet structures as Tim Berners-Lee’s Contract for the Web,79 Jemelniak’s involvement in something so far-reaching should be taken very seriously.

Lisa Lewin

Lisa Lewin is a newcomer to the board, assuming the trustee role in 2019 in addition to her work as co-founder and managing partner of Ethical Ventures, a so-called “change management consulting firm helping leaders build thriving organizations with a positive impact on society.”80 She hit the ground running, giving a talk at Wikimania 2019 with executive director Katherine Maher titled “Can Strategy Help Predict Our Future? Thoughts on Movement Strategy” referring to Wikimedia 2030, the Foundation’s aforementioned plan to make itself indispensable as the “essential infrastructure of the ecosystem of free knowledge.”81 With a background in education technology and teacher education, she also has plenty of connections to leverage in the Foundation’s mission to shoehorn Wikipedia into the classroom.

But it’s her day job that seems the most applicable to the Foundation’s current situation, in which reality stubbornly refuses to metamorphose into a future in which a gender-equitable Foundation sits snugly at the hub of 2030’s internet, doling out morsels of Wikidata to eager supplicants. Ethical Ventures sells a “strategy and change management” program that includes “growth enablement,” “reorganization,” “board engagement,” and - gulp - “leadership transition.” In a November presentation at the “All Tech Is Human” conference sponsored by regime change aficionado Pierre Omidyar’s Omidyar Network, Lewin suggested that when a tech company grows to the scale of a public utility - she used Facebook as her example, but Wikipedia clearly fit as well - its board members have a “moral duty” to consider how their platform affects its users, and to adopt “higher standards of care” if that platform puts the “safety of individuals, vulnerable populations, and democracy” at risk - especially if employees and management won’t do it. This advice seems tailor-made for Wikipedia, where gratuitous libel has cost its victims significant reputational capital. Could Lewin be the activist trustee arrived to save Wikipedia from itself?

Unfortunately, the rest of her speech indicated she was working for the other side. Lewin came down firmly on the side of thought-policing, citing internet security provider Cloudflare’s decision to deplatform anonymous imageboard 8chan - a longtime thorn in the establishment’s side - when it was alleged that a mass shooter had posted his manifesto there as a shining example to follow. “If we see a bad thing in the world and we can help get in front of it, we have some obligation to do that,” Lewin approvingly quoted the Cloudflare CEO in his come-to-Jesus moment, in which he violated the company’s content-agnostic policies out of misguided concern 8chan was inciting violence.82

But the Wikimedia Foundation and its trustees’ idea of a “bad thing” is often merely something they do not understand, or something that hurts the organization’s bottom line, dressed up in the language of morality. Seen through this lens, Lewin’s worldview is downright threatening, as it encourages board members to meddle enthusiastically in the strategic affairs of ‘their’ company if they get it into their head that the company is permitting some nebulous definition of “harm” to come to anyone. Is this what happened when the Trust & Safety division went over the heads of the Arbitration Committee to sanction the administrator Fram, despite the flimsiness of the “abuse” case against him? It has certainly laid the groundwork for a “leadership transition,” with several admins demanding trustee chair Maria Sefidari step down over her apparent conflict of interest, even though she claimed to have recused herself from that proceeding.83

Lewin has a few more interesting connections that the Foundation may wish to leverage. She sits on the board of the Center for Responsive Politics, which runs the OpenSecrets website tracking campaign contributions, giving her an inside eye on whose money is doing what in politics. She is also on the board of DoSomething.org, which purports to be the “largest non-profit exclusively for young people and social change.” Though its website is blanketed with photos of ebullient youth engaged in various forms of vigorous activity, the adults in the room - executives from Colgate-Palmolive, Snapchat, LinkedIn, JetBlue and Lyft, among others - are “legally and fiscally responsible for DoSomething.org.”84 DoSomething lets kids participate in clicktivism campaigns, share meaningless feel-good listicles (“11 facts about gangs,” 85 “11 facts about the Holocaust”86), while offering corporations a chance to expiate their sins by bestowing open-ended Opportunities on the Youth. It’s not easy to figure out exactly what DoSomething does, though it appears to be a platform for young people to launch and publicize awareness campaigns, which are in turn bankrolled by the group’s “sponsors.” These include the ubiquitous Omidyar Network, Johnson & Johnson (which hid asbestos in its talcum powder for decades and has paid out at least $325 million in damages to customers who developed cancer from its products),87 3M (currently mired in over 300 legal cases over knowingly releasing toxic ‘non-stick’ PFCs and PFAS into America’s waters;88 the highly persistent chemicals can now be found in 98 percent of the US population89 and will remain in the environment indefinitely, as they do not biodegrade),90 and General Mills (feeding your kids GMOs with a smile).91

Raju Narisetti

Raju Narisetti is the Wikimedia Foundation’s link to ‘new media,’ having joined in 2017 when he was CEO of Univision Communications Inc.’s Gizmodo Media Group. He left that company the following year, however,92 before it sold the Gizmodo portfolio to private equity firm Great Hill Partners, unloading Jezebel, Deadspin, Lifehacker, the Root, Kotaku, Splinter, and Jalopnik.93 The publications have clashed with their new private equity overlords, despite Great Hill insisting its new acquisitions would operate as “independent assets” within the portfolio. In August, Deadspin published a lengthy evisceration of its new master,94 alleging the interloper packed senior management with old colleagues in a sexist, diversity-deficient manner, covered sites in auto-playing video ads, micromanaged content and editorial (demanding writers be nice to the companies that bought those auto-playing video ads),95 and otherwise made such a huge mess that Narisetti actually weighed in on the agony of watching his erstwhile baby dismantled by the cold claws of private equity, telling New York magazine that Great Hill could “easily destroy the essence of these brands and the magic of longevity and relevance giving you sticky growth” by misunderstanding what made them valuable.96

As his old empire collapsed - Splinter shuttered in October,97 while the entirety of Deadspin’s newsroom resigned the following month along with its parent company’s editorial director in protest of its new master’s toxic micromanagement - Narisetti landed on his feet, becoming a professor of professional practice and director of the Knight-Bagehot Fellowship in Economics and Business Journalism at Columbia University.98 Under his watch, Gizmodo had collapsed in value from the $135 million Univision had paid for it to the much lower price - between $25 and $50 million - Great Hill did.99

Narisetti’s usefulness to the Foundation presumably lies in his media connections - before boarding the sinking ship that was Gizmodo, he was SVP of strategy at News Corp, Rupert Murdoch’s empire, where the Foundation claims his remit was “identifying new digital growth opportunities globally.”100 He also served a stint as managing editor of the Washington Post, dragging it kicking and screaming into the digital age, after 15 years with the Wall Street Journal. The Foundation received specific instructions after a 2014 “media audit” by Minassian Media - the shadowy PR operation run by Clinton Foundation communications officer Craig Minassian - to form closer bonds with “friendly” journalists;101 Narisetti is the perfect journalistic liaison for Wikipedia, having gotten important facts publicly, embarrassingly wrong amid an attempt to grandstand about the “slippery slope of press freedom.” He mistook Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, the ruling party of Pakistani PM Imran Khan, for the official news agency of India - where Narisetti grew up - in a tweet (their initials are the same, but their logos dramatically different, and one would expect quite different content from each), and was roundly mocked for it by people incredulous that a journalistic lifer could still make such rookie mistakes.102 Beyond a seeming reluctance to fact-check and a tendency to jump to conclusions regarding “freedom of expression” in his native land, Narisetti is a good fit for the Wikimedia Foundation because of his affiliations, which overlap extensively with some of the deeper pockets funding it.

He is vice-chair of the International Center for Journalists, a project of the Knight Foundation which offers journalism fellowships (including the one he oversaw at Columbia). The ICFJ is also backed by the Omidyar Network and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, but got a major cash infusion from Knight in 2018 to build up its programs to “combat the spread of misinformation and disinformation,” i.e. truths inconvenient to the organization’s paymasters. It boasted in a press release about launching fact-checking organizations in Africa and a plugin to alert Latin American social media users when they’d shared “discredited” articles. In more veiled terms, it bragged about “creating an environment that enables digital media startups - often the only independent news sources [in Latin America] - to thrive,” perhaps referencing its program to train Cuban journalists through an immersive Miami program103 or initiatives in countries like Venezuela whose socialist government’s excellent state-run media bristle with what well-behaved American journalists would deem “wrongthink.”104 Wikipedia plays a significant role in this type of initiative, having been used as a reputational barometer by social media platforms from Facebook105 to Youtube,106 as well as by Google,107 to determine what sources are “reliable” for the purposes of fact-checking.

Narisetti only lasted a year at Columbia, leaving in November to “pursue new opportunities in business publishing.”108 Wherever his career takes him, however, he will be touting Wikipedia as the solution to the problems facing journalism - even to the crisis of truth in the world. In a 2018 interview, he insisted “there has never been more urgency in Wikipedia’s 16-year history than now,” claiming self-perpetuating cyclones of fake news had engulfed hundreds of millions of people in such a way that “potential conflict” could be the result, and that Wikipedia was a “proven antidote” to such problems.109 Certainly free exchange of information is under threat by authoritarian governments and the monopolistic tech firms they have deputized to skirt pesky constitutional regulations, but Wikipedia is not an antidote to such incursions on civil liberties. Particularly if it is able to achieve the goals set forth in Wikimedia 2030, and insinuate itself into the fabric of the free internet, freedom of thought will have suffered a crippling blow.

Tanya Capuano

Tanya Capuano joined the Foundation in October 2017, the same month she joined real estate digital marketing company G5 as CFO. It’s not immediately clear how her past suited her for the job, and the generic name of her employer makes its own history difficult to uncover. Capuano was previously VP of finance at Intuit, overseeing the company’s financial software platforms, and worked in acquisitions and divestitures at Hewlett Packard after the obligatory stints in management consulting and investment banking.110 Hewlett Packard has tried to spin its work in illegally-occupied West Bank Palestine as somehow “reducing friction between Palestinians and Israeli soldiers at barrier checkpoints,”111 but the company’s operation of the apartheid-enabling BASEL biometric checkpoint system in the territory honeycombed with Jewish-only colonial outposts makes it complicit in the flagrant ongoing violation of international law those settlements represent. There is no evidence Capuano had anything to do with the West Bank project - HP acquired EDS Israel, the company contracted by the IDF to build that system, in 2009, four years after she left HP - but the acquisitions and divestitures division that employed her would have overseen that acquisition. It is also possible that the unnamed educational nonprofit boards she serves on were what drew her to the Foundation. Perhaps she is even that rarest of birds - a wholly innocent trustee on a very questionable board. If the latter, Capuano would be wise to ditch the position and never look back.

Postscript

Some might say putting the Wikimedia Foundation’s trustees under the microscope in this way is unfair, or that delving into the activities of the other organizations they work with borders on guilt by association. But the Foundation does all this and more when it allows agenda-toting editors to smear innocent people in its “encyclopedia” and refuses to take down pages that are clearly set up as repositories for libel, stitched together with imagination and liberally peppered with chutzpah, using guilt by association to fill in the gaps. Indeed, the Foundation prides itself on never taking a page down, and editors have openly admitted that asking to have one’s bio removed will result in further negative information being added.112 The Wikimedia Foundation and its representatives may bloviate about “free knowledge” until they’re blue in the face, but the platform is not about freedom - it is more about crafting reputational cages from which dissidents of any kind cannot break free and consigning them to the internet’s darkest penal colonies. The Foundation’s trustees may believe they are above the fray, but they are in fact the standard-bearers for the modern Ministry of Truth, the public-facing representatives of an organization that deliberately hides its true purpose under layers of jargon about making the whole of human knowledge available to everyone.

Add a comment

Read more: The Wikimedia Foundation’s Trustees: Missionary Footsoldiers in the War on Truth

- Details

- Written by Helen Buyniski

- Category: Wikipedia

Turkey’s Constitutional Court has ruled the government’s decision to ban access to Wikipedia in April 2017 was a violation of freedom of expression, a constitutionally-protected right. The decision represents a reversal of a Turkish court ruling from 2017 and comes just a month before an expected ruling from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), a body which has ruled against Turkey more than any other country in its purview. No timetable has been put forth for when Turks might regain access to the online encyclopedia, which had been blocked as a "national security threat" under Turkish law.

The Wikimedia Foundation, the nonprofit that owns Wikipedia, is doing a victory lap, congratulating the Turkish people on being reconnected with what it never stops reminding the world is the largest online repository of human knowledge. The Foundation bragged that despite the two-year blackout, it never caved to Ankara’s request to remove negative information showing Turkey "in coordination and aligned" with ISIS and other terrorist groups, information the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan denounced as a "smear campaign." Wikipedia, it boasted, would never give in to governments trying to quash free speech.

But there are more than a few holes in the Foundation’s version of events, starting with its boast that it stands for freedom of expression against repressive governments. While the Foundation very rarely obeys requests to remove information, whether they come from governments or individuals, it admits to having done so once. In 2014, the newly-installed US-backed Ukrainian government made a request to take down content on the English-language Wikipedia, and the Foundation acquiesced (it’s not clear what the information was). Why obey the dictates of Kiev but not Ankara? The puppet government of Petro Poroshenko was certainly no friend to free expression - its launch of a Ministry of Information Policy in December 2014 was widely ridiculed as a ham-handed censorship effort heavy on the propaganda, no different from Orwell’s “Ministry of Truth.” Thousands of journalists were doxxed through a site called Mirotvorets, declared “terrorist collaborators” for nothing more than obtaining accreditation from the separatist eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. As a result, at least 14 journalists had been killed by 2016, and many more were threatened and attacked. While some politicians advocated punishing the publishers of Mirotvorets, others called for revoking the press accreditation of the doxxed journalists and declaring them enemies of the state, and the Ministry of Information Policy itself praised the site for its "principled stance concerning defending national security."

This is not the behavior of a government that supports free speech. Yet Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales and the Foundation made no secret of their support for the coup that replaced Russian-sympathetic Viktor Yanukovych with the neo-Nazi Poroshenko government. Not only had Wales nominated a Ukrainian Wikipedia editor shot to death during the Maidan Square riots for ‘Wikipedian of the Year’ (without explaining how or by whom he came to be shot), but he would go on the record during the Yalta European Strategy conference of December 2014 calling on Ukrainian editors to skew the narrative in the Russian-language Wikipedia to retroactively whitewash the color revolution (and demonize Crimea's reunification with Russia). Russian Wikipedians, Wales said, deserved to be bombarded with “alternative views, alternative statements” - a.k.a. Trumpian “alternative facts” - through the supposedly-neutral encyclopedia.

Additionally, Turkish editors determined to circumvent Ankara’s ban on Wikipedia never really lost access to the site - it was a simple matter to use a VPN or other location-spoofing tools to read and edit to their heart’s content. Indeed, by blocking the average Turk’s access to Wikipedia, the government only ensured that whatever slander against Erdogan and his administration already existed on the site would metastasize, reproducing without interference by pro-Erdogan editors who might otherwise have pushed back against negative portrayals of the country. If anything, the ban handed control of Turkish Wikipedia to dissidents - a self-sabotaging move that may explain why the Turkish court was willing to reverse course on the ban. Others have speculated that the ruling by the Turkish court was meant to preempt yet another negative ruling from the ECHR, which never misses a chance to censure Turkey.

Turkey’s reasons for banning Wikipedia - the site wouldn’t remove information about government officials being involved with ISIS in trading oil, or about Turkey’s sponsorship of ISIS and other terror groups - are somewhat petty, as the information is true, no matter how negatively it reflects on Turkey. For all that Wikipedia is positively bristling with libel about any government that has gotten on the bad side of the US, UK or Israel, the relationship between Turkey and ISIS is real. While Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the US provide funding, weapons, protection, and PR, Turkey assists in the movement and protection of people and supplies - and oil. If Turkey didn’t want the world learning about their support for terrorists, they might have thought of that before getting into bed with the governments that have done more than anyone else to unleash chaos upon the region.

Even if Turkey is in the wrong, however, for the Foundation to cry “freedom of expression” is disingenuous when it is willing to give other countries a pass on their own human rights violations, even working with them to oppress their populations. The case of Wikipedia in Kazakhstan is an instructive example of what a repressive government can do when it cooperates with the encyclopedia, instead of kicking it to the curb. In March 2011, a month before Kazakh dictator Nursultan Nazarbayev changed the country’s official language from Russian to Kazakh, a group of Kazakhs bankrolled by the ruling family operating under the name WikiBilim began transferring material from the government-sanctioned Kazakh encyclopedia into the Kazakh-language Wikipedia. WikiBilim soon arranged with the Wikimedia Foundation to have all 15 volumes of the encyclopedia piped in, overwriting the work of any Kazakh Wikipedia editors who might have thought they were entitled to something more than the government-approved version of reality.

Wales didn’t merely allow the Nazarbayev regime - which has been repeatedly sanctioned by the ECHR for human rights violations and which has a lengthy track record of jailing and even killing journalists critical of the government - to seize control of the Kazakh Wikipedia. He declared Rauan Kenzhekhanuly, director of WikiBilim, Wikipedian of the Year and awarded him a $5,000 prize. Wales for years insisted WikiBilim was an independent organization, but when it later emerged that he had discussed the project with the group’s government patron at Davos the previous year, he was left scrambling for excuses. When Kenzhekanuly, a former government official, was appointed governor of the Kyzylorda region in 2014, Wales finally gave up on pretending everything was kosher in Kazakhstan, implying in a Reddit Ask Me Anything the following year that he’d been tricked into assisting the repressive regime.

Kazakhstan is only one of the countries that has received the Foundation and Wales’ stamp of approval despite (because of?) an adversarial relationship with freedom of expression. Wales is married to the former diary secretary of Tony Blair, who has followed up his warmongering stint as British PM with a lucrative lobbying career, hopping from one despot to another to help them whitewash their human rights records and reposition themselves as ripe for foreign investments. The United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Azerbaijan, and Israel have all fostered friendships with the Foundation to various extents, despite atrocious track records in human rights. For the Foundation to cry foul in Turkey’s case is hypocritical in the extreme - Erdogan's crime, in their eyes, is not jailing journalists but failing to work out a lucrative agreement that would allow him to whitewash his human rights record by lining the Foundation's pockets. Wikipedia no more supports free expression than Turkey fights terrorism.

[need more information about what Wikipedia is? start here...]

Add a comment- Details

- Written by Helen Buyniski

- Category: Wikipedia

[originally published Nov 7 at PRN.fm - reposted for anyone who came here from Kevin Barrett's excellent False Flag Weekly News, where I was interviewed this week]

Wikipedia is one of the most popular websites in the world. It’s free, it’s educational, and it’s democratic — what’s not to like? The average user has no reason to think the material it publishes is anything but true, and it has become the go-to authority for anyone looking to quickly educate themselves on a topic. Qualifications and expertise are beside the point — this is an open-source repository of all human knowledge, and surely the cream rises to the top; if information is wrong, surely editors are standing by to correct the record.

But as Andrew Lewis said, “If you’re not paying for something, you’re not the customer; you’re the product being sold.”¹ Our in-depth investigation has found that everything we’ve been led to believe about Wikipedia is a lie. Wikipedia serves as a warning that if something sounds too good to be true, it isn’t true. Scratch the surface of the “free encyclopedia anyone can edit” and you find a finely-honed propaganda machine manipulated by experts and used to destroy the reputations of those who dare question the status quo.

The casual user sees the “edit” button next to an entry and assumes all users can make changes on an equal footing. In reality, many areas of the encyclopedia are tightly controlled by ruling cliques operating with the blessing of Jimmy Wales, the co-founder and self-styled “benevolent dictator” of Wikipedia. The experience of trying to correct information about oneself on Wikipedia is akin to being trapped in a Kafka novel — enclosed by an impenetrable thicket of unevenly-enforced rules, subject to the whims of powerful groups that officially do not exist, helpless to stop millions of Wikipedia users from happening across false and even libelous information about yourself or your work. For those trapped in Wikipedia’s internet gulag, there is no escape — not even deletion. Wikipedia, Wales gloats, does not believe in the right to be forgotten.²

While Wales has said he considers his role akin to that of a constitutional monarch — largely ceremonial but ultimately powerless³ — he has the ability to override the actions of any other user and has deployed these godlike powers to shape the narrative. Favoritism, rules enforced unevenly, pay-for-play editing, ideological hit squads, hundreds of factions conspiring to various degrees of secrecy to game the system — all this goes on with Wales’ blessing. A case can be made that the Wikimedia Foundation has violated its charter as a non-profit and stripped itself of the immunity conferred by section 230 of the Communications Decency Act by involving itself editorially in the content it hosts, by choosing which editors are allowed a platform, and by choosing when and where to enforce its rules.

J’ACCUSE

Jimmy Wales did not create Wikipedia, though he has edited his biographical article more than half a dozen times to give the impression that he did. Larry Sanger, whom Wales attempted to airbrush out of history, left Wikipedia in disgust soon after its launch: “Wikipedia never solved the problem of how to organize itself in a way that didn’t lead to mob rule. On the one hand, it isn’t a mob at all. It’s highly organized and structured and there’s a lot of rules…But on the other hand, the way that the community is organized isn’t codified or decided upon in any type of constitutional way. So there might be some people who selectively apply rules according to positions that other people take on their pet issues. And that’s inherently unfair.”⁴ The inmates have taken over the asylum, and they are running it with the blessing of Wales himself.

Wales may not have founded Wikipedia, but as its public face he has influenced the character of the site more than anyone else. It is his face users see during the fundraising campaigns that bring in far more cash than the site requires to operate — $89 million last year⁵ — fueling the growth of an unaccountable bureaucracy, top-secret projects hidden from the Wikipedia rank and file, and an increasingly detached sense of responsibility for the very real harms caused by its contents. Wikipedia has allowed itself to be weaponized to do the dirty work of the ruling class, and anything that deviates from the establishment line is fair game to be smeared, attacked, and destroyed.

Wikipedia’s elite operates in secrecy. In general, the more a user or group on Wikipedia protests that there is no “cabal” of powerful editors running the show, the more likely they are to be members of it. Wales himself joked about forming a “cabal” to enforce policy back in September 2001 when the site was just getting off the ground.⁶ His idea became the Arbitration Committee, which some have likened to Wikipedia’s “supreme court.” Skilled in navigating the dense thicket of rules that has grown up around Wikipedia, ArbCom and the hundreds of administrators who form the next layer of bureaucracy are able to control what remains on the encyclopedia and what (or who) is deleted. If these powers were wielded fairly, their influence would be welcome — but the rules are instead used as a cudgel to enforce ideological conformity.

Wikipedia isn’t just dismissive of expertise –it’s actively hostile to experts. While one of the site’s many policies discourages editors from removing something just because they dislike it (WP:IDONTLIKEIT), Wales and the ruling don’t-call-it-a-cabal have made an exception for themselves. From the beginning, Wales surrounded himself with a cadre of admirers willing to do his bidding — editing his biography when his own self-editing was exposed (and then editing it again to remove a paragraph about the self-editing),⁷ or attacking his enemies when they ask difficult questions on his talk page — and these internet hitmen became Wikipedia’s ruling class — shaping narratives made to order and serving them up as more real than reality.

ABUSE OF NONPROFIT STATUS

The IRS forbids 501(c)(3) organizations like the Wikimedia Foundation from participating in political campaigns “on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office,” a ban which extends to “contributions to political campaign funds or public statements of position (verbal or written) made on behalf of the organization in favor of or in opposition to any candidate for public office.” IRS policy clearly states that “violating this prohibition may result in denial or revocation of tax-exempt status and the imposition of certain excise taxes.” The policy further explains that “voter education or registration activities with evidence of bias that (a) would favor one candidate over another; (b) oppose a candidate in some manner; or (c) have the effect of favoring a candidate or group of candidates, will constitute prohibited participation or intervention.”⁸

The Wikimedia Foundation has dipped its toe into political waters on several occasions. Management is aware of the perils of getting politically involved — one of the first major Wikipedia scandals broke in February 2006 when it was discovered that US Congressional staff were scrubbing the biographies of their politicians — removing broken campaign promises,⁹ scandals, and other undesirable details and adding “glowing” tributes and favorable information.¹⁰ At the same time, negative information was appended to the biographies of their opponents, and some ambitious staffers were replacing their candidates’ biographies wholesale with staff-authored versions. Wikipedia responded initially by banning Congressional IP addresses, lest the site appear to be complicit in the political self-promotion, which would have torpedoed their nonprofit status.

When Google search results returned “Nazism” as the ideology of the California Republican Party just a week before that state’s primaries earlier this year, Google blamed Wikipedia, explaining that the Google “knowledge box” that contained the offending term is often populated with Wikipedia text.¹¹ The “vandalism” had remained on the party’s Wikipedia page for six days before it was corrected, hidden in a “piped link” where the link text and “alt text” read differently; meanwhile, other edits were reverted within a few minutes, suggesting this one was allowed to persist, deliberately hidden so it would only appear in Google search results.¹² Whether or not it was deliberate, it is not the first time Wikipedia has appeared to promote the neoliberal wing of the Democratic Party.

Such apparent political bias makes more sense in light of the fact that the Wikimedia Foundation contracted the Minassian Group, run by Clinton Foundation Chief Communications Officer Craig Minassian, to train Wikimedia’s own C-level employees, directors and managers in media strategy for the year 2014–2015.¹³ Minassian was further tasked with conducting a “communications audit” in 2016.¹⁴ Some editors among the Wikipedia rank and file were unhappy about having their territory politicized,¹⁵ particularly given how much of Wikimedia’s money was going to Minassian — $436,104 in 2015 and $406,957 in 2016.¹⁶ While the details of Minassian’s activities are not public, the group did issue a report detailing its audit findings, which primarily consisted of parsing media coverage by subject, country, publication, and author and ranking outlets in terms of prestige. Wikipedia was advised to focus on portraying itself as trustworthy and neutral in the media even while “seeking out and dispelling controversial issues.” The audit recommended concentrating on building a rapport with “friendly” journalists writing for what Wikipedia’s editors would call “reliable sources.”¹⁷ Minassian has a history of planting stories favorable to the Clinton Foundation in “friendly” media, as WikiLeaks revealed in its Podesta emails dump, which included a message from Craig Minassian himself boasting of favorable coverage he had secured for the foundation on the Colbert Report.¹⁸

Wikipedia editor SashiRolls linked the Minassian hire to the arrival of a crew of militant editors on the Clinton Foundation article who kept it scrupulously clean of any mention of the billions of dollars the Foundation took in for victims of the Haitian earthquake but never distributed to victims, opting to construct a lucrative industrial park in an undamaged area of the island instead.¹⁹ Clinton’s own Wikipedia article is similarly spotless, bearing only a sanitized summary of her “email controversy” and no mention at all of the revelations from WikiLeaks’ DNC and personal email document dumps. No mention is made of the invasion of Libya on false pretenses or the fallout from that invasion — indeed, reality is directly contradicted with a mystifying sentence reading “there was a trend of women around the world finding more opportunities and in some cases feeling safer, as the result of [Clinton’s] actions and visibility,” sourced to a book called The Hillary Doctrine. The article is “protected” — frozen so that only high-level administrators can make changes — and includes the option to listen to it as audio, indicating it will stay frozen in that state.²⁰

The efforts of a clique of ideologically-motivated editors to whitewash political entries are of particular interest given the deployment of such teams on other social media sites like Facebook, Reddit, Instagram, and Twitter during the 2016 election. Clinton strategist and fundraiser David Brock’s Correct the Record (CTR) superPAC spent at least $1 million during the election to “push back against” negative posts about Clinton as part of a program called “Barrier Breakers,”²¹ and it’s unlikely that such an operation would have overlooked Wikipedia, which other social media sites often use as a fact-checking tool. Brock has come under scrutiny before for bending campaign finance rules — superPACs aren’t supposed to participate in individual elections, and Media Matters for America, the organization for which he is best known, is a 501(c)(3) and therefore barred from conducting political activity on behalf of any candidate,²² much like Wikimedia. A former CTR contractor estimated the group’s expenditures at $5–6 million as of August 2016 in a post on 4chan in which he encouraged others to sign up for easy cash, explaining that CTR employees were given high-ranked and backdated accounts on Reddit and Twitter so as to more easily blend into the discussion.²³ Infiltrating Wikipedia is even easier — editors can change usernames and sometimes choose to leave their history with a previous username behind, especially if it was associated with disciplinary sanctions, as ideologically-motivated editors’ often are. Any Wikipedia editor who attempts to look into this sort of infiltration can find themselves indefinitely banned from the site, as SashiRolls found when he tried to blow the whistle on Sagecandor, an editor who racked up hundreds of edits on articles related to Clinton’s 2016 campaign around the time of the election — 904 edits to “fake news websites,” 631 edits to “Russian interference in the 2016 election.”²⁴ Sagecandor, implying that SashiRolls was part of a Kremlin disinformation campaign,²⁵ had him hauled before Wikipedia’s disciplinary committee, where he was accused of “wiki-hounding” and indefinitely banned from editing. Sagecandor and his allies continued to smear Sashi while he was prohibited from responding, until another administrator found incontrovertible proof Sagecandor was in fact a “sockpuppet” of a previously banned user — vindicating SashiRolls, but too late, as he remains banned.²⁶

“Charitable organizations” like Wikimedia are also barred from operating for the benefit of “private interests,” with no part of a group’s “net earnings” accruing “to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.”²⁷ Yet Wales used his Wikimedia credit card so much that he was relieved of it in 2006, after it was revealed that he was billing $1,300 steak dinners and other outsize expenses to the “charity.”²⁸ At one point he was on the hook for $30,000 in expenses billed to the Foundation for which he could not show receipts; he reportedly reached an agreement with the Foundation’s lawyer to pay less than a third of that. More recently, Wales took the results of Minassian’s audit, which the Wikimedia Foundation paid for, and used it as the business plan for WikiTribune, pitched as a scrupulously neutral news platform helmed by “friendly” journalists and supported by an army of volunteer editors and fact-checkers. The professional journalists would be funded by reader subscriptions, while the volunteers would operate much in the manner of Wikipedia itself. WikiTribune’s mission? To combat “fake news.”